The main import of a pre-emption right is that the prospective seller is required to inform the other co-venturers that it wishes to transfer its interest in a licence/lease to a prospective purchaser and such notice will contain the principal terms of the deal agreed with the prospective buyer.

Before the prospective seller can complete the sale to the intending buyer, it must ensure that the other co-venturers do not want to purchase the interest in question on the same or equivalent terms. If they do, the intending seller must sell the interest in question to those other co-venturers, who have exercised their right to buy.

Pre-emption rights were invented in furtherance of a traditional view that co-venturers, who have chosen to exploit a licence together, should have advantages in relation to each other’s shares in the licence over prospective newcomers, who may wish to obtain rights under the licence. The consequence of a pre-emption clause is to permit the participating interest holders to exclude new entrants, rather than allowing interests in the licence to go to outsiders.

Forms of pre-emption Rights

There are different forms of pre-emption rights found in many Operating Agreements. The first and most common form is a requirement on the seller to offer the other co-venturers a deal equivalent to that, which has been agreed with a buyer – reflects a true right of pre-emption. This appears to be the form contained in a typical JOA used in Nigeria. Such a right does not come into effect until after the end of the negotiation process by which time a potential third-party purchaser has spent substantial time and money. This form is harsh and as a result of its uncertainty has the potential to discourage a prospective purchaser, who will ultimately incur huge losses should any or some of the co-venturers eventually exercise their right of pre-emption.

Consequently, a common alternative and less burdensome is a right of first refusal. This places an obligation on the seller to offer the asset to its co-venturers first before negotiating with third parties. A third form and more liberal approach is one that places a lesser right on the part of the co-venturers to enter into a negotiation with a prospective seller for a certain period of time after which the seller can assign the asset freely to any third party of its choice. Pre-emption rights usually apply only to asset transfers and hardly apply to a change of control through the sale of shares.

Challenges of pre-emption clauses

The most common form of pre-emption provisions later became unpopular as a result of the difficulties, uncertainties and delays encountered in the disposal of upstream oil and gas assets. In UK, it led to the setting up of a Committee known as Progressing Partnership Working Group (PPWG) under the auspices of PILOT, a body that facilitated a partnership between the oil gas industry operators and the government in promoting UKCS competitiveness. The Report of PPWG articulated the problems of pre-emption rights as follows: parties to pre-emption rights often do not declare their intentions until late in the process thus creating uncertainty,

(2) Pre-emption provisions often require a fully executed sale and purchase agreement before it can be invoked thereby taking the significant time of the purchaser and resources before knowing if pre-emption is likely, and (3) deliberation period takes up to 90 days thereby prolonging the period of uncertainty and time required to complete the transaction. The Report also laid the foundation for a robust legal and contractual framework for investment in oil and gas asset divestment and acquisition in the UK including the introduction of the innovative Master Deed regime.

Mechanisms to circumvent pre-emption clauses

Consequently, draftsmen invented a number of mechanisms to circumvent the application of pre-emption provisions. The prominent of these devices are the concepts of the unmatchable deal, affiliate route and package deal. However, the effectiveness of these mechanisms cannot be guaranteed with a water-tight prediction as the Courts may interpret the pre-emption clause in a way that secures the commercial intention of the parties which may not recognise any of the mechanisms.

A Review of typical JOA pre-emption clause used in Nigeria

As indicated earlier, JOAs used in Nigeria follow the common form, which requires a seller to offer the other co-venturers a deal equivalent to that which has been agreed with a buyer. A typical JOA in Nigeria would have the following provisions:

(a) …., if any Party has received an offer from a third party which it desires to accept, for the Transfer of its Participating Interest hereunder (the “Transferring Party”), it shall give the Non – Transferring Party prior right and option in writing to purchase such Participating Interest …

(b) The Transferring Party shall first give notice to the Non – Transferring Party specifying therein the name and address of the aforesaid third party and the terms and conditions (including monetary and other consideration) of the proposed Transfer.

(c) Upon receipt of the notice …the Non – Transferring Party may within thirty (30) days thereafter, request in writing the Transfer of such Participating Interest to it, in which event the Transfer shall be made to it on the same or equivalent terms.

(d) Where the Non – Transferring Party does not request the Transfer of such Participating Interest as requested above, the Transferring Party may, within a period of one year thereafter Transfer it to the said third party provided that an instrument evidencing such transfer must be executed by the parties hereto and submitted to the Non-Transferring Party.

(e) Provided always and it is hereby agreed that nothing in this provision shall preclude any internal restructuring of a party to enhance efficiency or offering its shares either by way of public offer, private placement, rights issue or creation of debt instruments as means of capital raising and/or listing the party’s shares on an investment exchange (s).

The pre-emption right highlighted in paragraphs (a) to (d) above falls within the form that creates uncertainty and risk to a prospective buyer as the pre-emption right is activated after a deal has been agreed upon between a transferring co-venturer and a third party and after the third party must have expended huge resources and time in negotiating the deal. The would-be buyer will have to wait for a period of 30 days to ascertain its fate in the transaction. In a situation where one or more of the co-venturers exercise their right of pre-emption, the prospective buyer goes home empty-handed but if otherwise, it can then proceed to close the deal with the transferring co-venturer.

There is, however, a reprieve to a prospective buyer as it can be able to acquire participating interest in an acreage if the deal is structured as a share sale transaction. Paragraph (d) above excludes the internal restructuring of a co-venturer by way of share sale and transfer arrangement from the pre-emptive purview of the JOA. To this end, it would appear that any transaction that follows the corporate sale route through share acquisition would not be caught by the requirements of paragraphs (a) to (d) above. It would appear that by the combined provisions of Section 95(1) & (3) of the Petroleum Industry Act, 2021 (PIA), the transaction would be regarded as a change of corporate control transaction, which the PIA treated as an assignment that requires Ministerial Consent for it to be effective. Consequently, it would seem that the only hurdle to effectively complete the deal is to receive Ministerial Consent over the transaction.

Conclusion/Comments

Given the uncertainty and the risk inherent in the pre-emption right provisions stated above and considering the current appetite by the IOCs to divest their assets in Nigeria and focus on other core business interests, it would be expedient for the government and the industry to come up with a streamlined regime that removes barriers and uncertainties created by a typical JOA pre-emption Clause as was done in the UK when the country was confronted with a similar situation.

This will undoubtedly incentivise oil and gas assets trading in Nigeria and enhance the competitiveness of the Nigerian oil and gas industry as it will give investors the confidence and comfort that their transaction would not be aborted after investing time and money in negotiating a deal. This will indisputably attract the right investors willing to increase their portfolio or launch their entrance into the Nigerian oil and gas industry through an asset acquisition window. It will also avoid the scenario and recourse to any speculative mechanisms discussed elsewhere as a way of circumventing the effect of a pre-emption clause. It is, therefore, necessary for the pre-emption clause in new JOAs to be reviewed to address the shortcomings inherent in the current JOA.

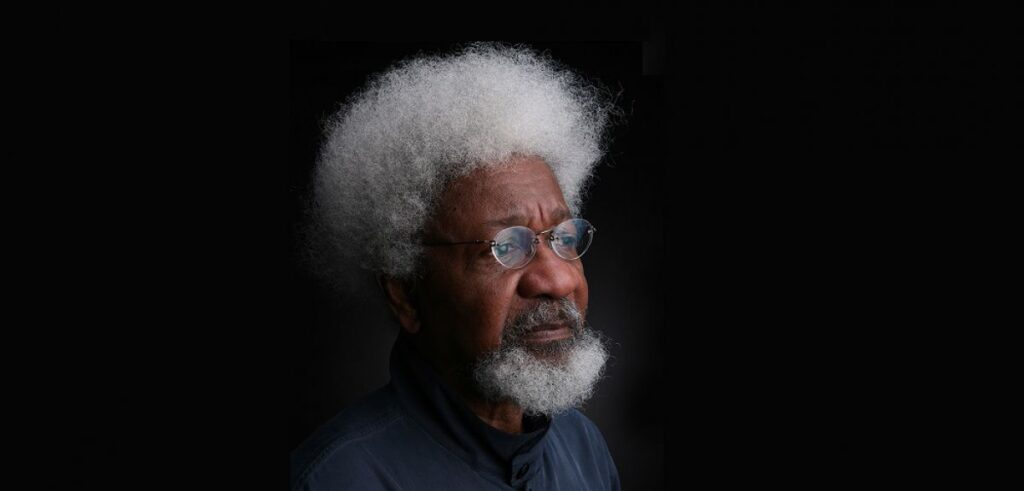

Ibebuike is a partner, Creed & Brooks, Lagos.