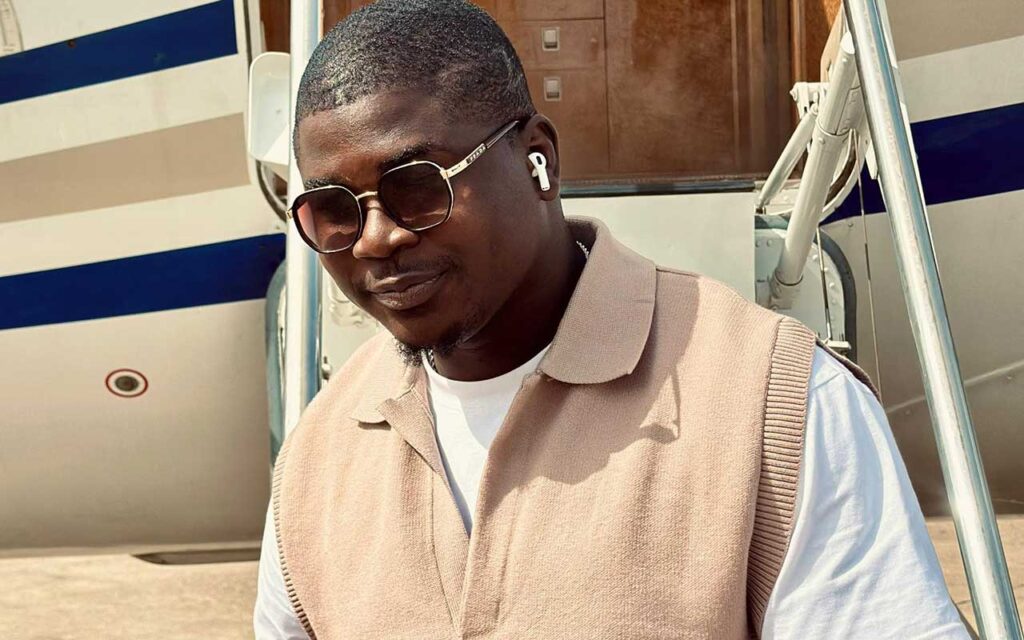

Gregory Nnamdi Nnabike Mbajiorgu stood by the side of a vehicle at Peace Mass Transit Park in Nsukka. He was waiting for the guest of renowned sculptor, Professor Emeritus, El Anatsui, who was being installed as Ikedire of Ihe In Nsukka, the day after. It was the first time the two arts and culture personalities were meeting. The theatre teacher was warm and he spoke encouragingly of arts, theatre practice and journalism. Even as he drove through the road from the park to the University of Nigeria campus, he ensured the guest of Anatsui settled down before he wearily went home to rest.

In the morning, he brought a copy of the book he co-edited with Professor Amanze Akpuda titled, 50 Years of Solo Performing Art in Nigerian Theatre: 1966-2016, which chronicles 50 years of solo performances in the country. “I want you to read this book, and give me your impression; if any correction, let me know. You can review it,” he said.

“I will,” El’s guest responded.

Much later in the evening, after the chieftaincy ceremony ended, Mbarjiogu took the guest through his life as a solo performer.

Born May 24, 1964, the Associate Professor of Theatre and Film Studies at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka is an established mono dramatist, who had solo-performed his first play, The Prime Minister’s Son, many times both inside and outside of Nigeria.

“I was inspired and influenced by the pioneering performance of Wale Ogunyemi (in Samuel Beckett’s Acts Without Words), Tunji Sotimirin’s performance of his comic solo sketches (Molue) and Fusho Alabi’s late 80s performances of his compilation of Luther King Junior’s speeches (Martin Luther King remembered),” he said.

He, however, added, “the difference between me and these pioneers is that I transcribed the recording of my performance and got it published after nine years of improvisatory tour of all parts of Nigeria – with the publication of my solo. The Prime Minister’s Son, attracting numerous scholarly attention and other actors performing the same play, it became even more popular.”

The academic can hardly write if he is not motivated, and he is only motivated by reading, research, observations, or interacting with those in the environment of his interest. “After drawing inspiration from the above sources, I draw and outline of my story sequence and then I begin to add flesh to the skeletal out line, slow by slow, step by step until the story takes a sensible shape,” he said.

His journey into mono drama came as a result of his desire to prove to his father that theatre arts was his passion and not mass communication, which his father wanted him to study. He was also betrayed by the lack of enthusiasm showed in starting a performing company. He scripted his first play, The Prime Minister’s Son, which eventually brought him to prominence in solo dramaturgy.

Solo dramaturgy, you ask?

Mbarjiogu smiled, “because most actors, like flocks, are trained to follow their shepherds, and like the flock always moving as a team, they are not likely to think independently. Most training institutions train actors to function in a convergent mode. Only a few of us ruled by our critical intelligence resist such convergent orientation by thinking out of the box and by so doing, awaken our ability to function independently and create on the spur of the moment. And by so doing, energise our ability to instantly function in the divergent mode.”

The 1990 graduate of Dramatic Arts, UNN, said that he is a solo dramatist doesn’t mean he abhors multicast production or he always functions alone. “My drama on climate change is a multicast production, same with most of my plays; my experiment in solo drama stands out because it shot me to limelight at the early stage of my career. I have directed Wole Soyinka’s A play of Giant, Ola Rotimi’s Hopes of the Living dead, Femi Osofisan’s Midnight Blackout, Esiaba Irobi’s Nwokedi, Colour of the Rusting Gold, Ahmed Yerima’s Hardground and Chris Iyimoga’s Son of a Chief, to mention but a few.”

The success of The Prime Minister’s Son as a solo-dramatic text motivated several Nigerian playwrights to take interest in scripting their own solo plays. The play served as a model for some, even “Sotimirin had to transcribe and publish his improvisatory solo that had long existed in the context of performance. Some wrote their solo plays and forwarded it to me for editorial input, others were able to create their own solo plays after attending my extensive solo performance workshops, with time, it became absolutely necessary to compile, re-edit and publish our harvest of solo plays.”

After producing a play, The Lion on Exit, for the send-forth ceremony of the former Vice Chancellor of the University of Nigeria, Professor Chimere Ikoku, in 1992, Mbajiorgu was employed in June 1993 in Drama as a graduate assistant. He grew through the ranks until attaining the status of a reader or associate professor of Theatre Arts in 2017.

Mbajiorgu also produced a documentary theatre on the poems and speeches of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe entitled, The Hero of Heroes/ The Lion of Lions. This was commissioned in May 1996 as one of the Federal Government approved cultural presentations during the funeral activities of Nigeria’s first indigenous president.

In 1997, he wrote a playlet, Trial of the Fittest, which was performed at the Bridge Water Hotel, Enugu, for the end-of-year retreat of the African Institute for Applied Economics, AIAE. He was also contracted in 2003 to create a drama on resolving water conflicts by the Office for Environmental Protection/JDP Water Programme in Enugu, with financial support from MISEREOR in Germany. He produced Wota na Wota, which is co-authored with professor Chike Aniakor.

During the National Universities Games (NUGA) in 2008, the play had its first global premiere at the Arts Theatre of the University of Nigeria.

In 2023, he edited the 420-page book, The Power of One: An Anthology of Nigerian Solo Plays, which comprises 16 works, including his The Prime Minister’s Son and, The Gadfly by Ahmed Yerima.

His latest work was ignited by the desire to mainstream the teaching, learning and production of solo drama in Africa, to produce the needed work book for earlier edited theoretical seminal text, 50 Years of Solo Performing Arts in Nigerian Theatre – 1966-2016, to inaugurate Africa’s first Anthology of solo plays, and by so doing, “arrest the fleetingness of oral – based solo performances in Nigeria and prove that solo drama has its place as a sub-genre of dramatic literature. With this singular anthology, we have succeeded in institutionalising solo dramatic literature in Africa, thus, ensuring that this form of playwriting is preserved for the future generation.”

This anthology has, at last, “helped to satisfy the yearnings of all our followers and fans, who for long, have been expecting us to produce this compendium,” Mbarjiogu confessed.

On the process of adapting an existing improvisatory performance into a solo play, he confesses, “the method is simple, you first record the improvised performance, then you transcribe from the video recording- after a successful transcription, you will observe that the skeletal text on paper will require literary embellishment to appeal to the reading audience, from then on, you will keep improving on the blue print until it satisfies critical standard. Then you send it out for further proof reading and editing. It is after all these rigorous processes that it goes to the publisher.”

He is satisfied with the final version of The Prime Minister’s Son, “but my co-authored solo play, Beauty for Ashes, will perhaps get a revised edition after its premier production as the first Nigerian gospel solo scripted for evangelical purposes. I am hopeful to stage our gospel solo soonest. For now, I am busy scripting my first solo play on climate change with focus on how climate plays out in a family.”

Mbarjiorgu already has it at the back of his mind that a character he is depicting on stage must be true to type and true to life in line with the conventions of stage reality, that is, “my character or theatrical elements must be adaptable to stage realities, my characters must suggest what cannot be enacted on stage considering the limitation of live theatre, selecting only those realities that do not contravene the conventions of life theatre. For instance, I consider it crude presenting stack nudity or sexuality on stage or shading real blood on stage, be it the blood of a human or an animal.”

He added, “the secret of my growth and success in the theatre industry stems from my high reception to criticism. No artist can progress without being open or yielding to criticism. We grow further and further in our art by allowing others point out our weaknesses. It takes humility on our part to be fully open to criticism.”

When working with actors, he gets them to understand basics of characterisation, asking study questions such as, who is the character? What are the characters circumstances? What are the characters objectives? What is the character willing to do to accomplish such objectives and related questions. “Knowing who the character is helps you know what the character will do in any given circumstances,” he retorted.

One of the challenges of modern theatre is how to get young ones to see productions, considering alternatives like cinema and watching movies at home. Mbarjiogu has a solution. He said: “First, your material must appeal to the young stars. And if you think your theatre will be a hard pill for them to swallow, then you must serve it like the sugar coated pills. Sugar coated pills in this case would imply lacing your story line with cultural indices that appeal to the young stars.”

For him, the best plays are written with a sense of stage, according to him, “when I am reading a play and I perceive the characters jumping out of the page, I develop an urge to produce such a play on stage. Good plays don’t just read well, you must feel the pulse of the characters even at the reading stage. No good play is written in a hurry. Even when such plays are written in a short period, the gestation period must have been over a year or more.”

August Wilson inspires him a lot as a playwright, and his best play for him is The Piano Lesson. Why? “Because of the way he weaves the complex tale of his background of racial prejudice in a minimalist setting, comprising the old man, the piano and the little child learning both how to strike the keys on the piano and the lessons of his ancestral pasts in one bit.”