No doubt, ‘photopoetry’ and its various alternatives — photopoème, photoetry, photoverse, photo-graffiti, among others — as a genre of literature is growing by the day.

No doubt, ‘photopoetry’ and its various alternatives — photopoème, photoetry, photoverse, photo-graffiti, among others — as a genre of literature is growing by the day.

‘Photopoetry’ is an art form in which poetry and photography are equally important as medium of communication. As the name suggests, it’s a combination of photography and poetry. The goal is to create a piece that is greater than the sum of its parts, where each element enhances the other to create something truly special. The photograph can be used to illustrate the poem, while the poem lends meaning and emotion to the image.

As a form of artistic expression, both poetry and photography provide a narrative that is desired certainty without being descriptive. She explores the relationship between poem and photograph can both perpetuate and subvert representations of the objectified other. From a photographic perspective, examining how, in the absence of any discernibly modernist photopoetry book, the most important dialogue between poem and photograph was enacted within Imagist verse. It proceeds to examine the introduction of urban environments into early-to-mid-twentieth-century photopoetry.

Temilade Adelaja, a Nigerian photographer and writer, is one artist, who has taken this genre to a great height. Recognised across Africa, in the UK and the US, Adelaja art moves between poetry and prose, providing a convoluting concourse of variegated actions juxtaposed. She encumbers her photographs with literature thereby crafting a thematised concept for her works.

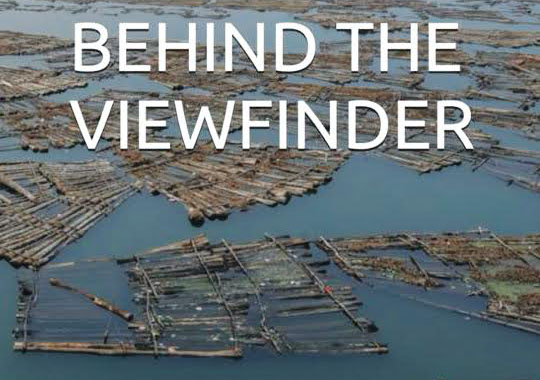

In her new work, Behind The Viewfinder, Adelaja deploys a narrative, which relies on the flow of relationship between the lens and words.

This collection has an autobiographical feel with the camera as the element of communication: composition, language, light, sound, space and narrative.

The book transit through epochal moments until it finally reaches the point of anagnorisis. From Cry Me A River to Nigerian Batman and Casting The Net, among such others as, Silent Sentinels, Market Place: Red Pulps, Black Magic, Guardians Of The Emir, Lagos Labyrinth, Lofty Aspiration, The Liar Of The People, Melodies Of Memories, The Beach’s Cry, Rising Waters, Market Inferno, Street Ball Symphony, Tranquil Twilight, Chibok Girls Beneath The Bridge, Casting The Net, Silent Sentinels, Market Place: Red Pulps and Black Magic, it features themes that explore the connections, potentials and co-habitations of poetry and photography, where collaboration enhances each medium whilst evoking what makes them so uniquely compelling.

From the perspective of a photographer, Adelaja resurrect socio-realistic themes and memories of poverty and loss nature. Through an eclectic mix of topics, this collection offers insight into the experience of life, with all its complexity and emotions.

The style of this collection is free verse with the subject matter taking a realist approach. Each poem is like a mirror. It reflects life in non-structured, conversational tones.

In Dance Through The Lens, the author finds inspiration and meaning in photographic expression: the refuge and resilience, “embracing the beauty of the human spirit in its most authentic form.”

Despite the lack of dancing prowess, the lens becomes the author’s companion in her desire to dance, as just a few clicks immortalise memories and evoke emotions.

Watching the mesmerising twirl, somersault and backflip with precision and grace, the lens creates a seamless performance that captivates the onlooking crowd.

Reflecting on Yoruba folklore, the author notes that the deity, Sango, finds solace through dance, symbolising its transformative power beyond mere artistry.

“Dance breathes life into the soul, offering solace and liberation in times of hardship. It transcends barriers of shyness and fear, nurturing growth and resilience,” the author says.

In Cry Me A River, she eulogises the onion, saying, its essence delights:

Similar to her soulful melody is a vegetable,

One that evokes tears from both man and woman,

As its layers of flavour are unveiled.

Like unwrapping a gift, cutting through its core,

I shed tears of joy with every savoury bite,

Whether sautéed or caramelised, its essence delights,

In every dish, its taste divine, a culinary marvel through time.

The theme of protests against injustice is captured in Political Procession, where she remembers the incident of police brutality by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), and Nigerian youths had to mobilise to demand disbandment of this unit through protests.

In works such as, Siesta In Makoko and My House Is A Boat, nature is the concern of Adelaja. Deploying both prose and poetry, she interrogates the themes of nature from different perspectives and styles.

In Siesta In Makoko, she writes: “During one of my visits to the Makoko – one of Africa’s most unique inner-city slums, in the humid summer heat of Lagos, a serene sight caught my eye — a young man resting peacefully amid the tranquil beauty.

The gentle lapping of the water against the bamboo bed, the warm embrace of the sun accentuating his radiant melanin, and the harmonious symphony of nature enveloping him in its embrace — it was a moment of pure bliss and tranquility, a respite from the daily hustle and bustle.

“As the water flowed gently, it seemed to carry away his worries, washing them downstream and leaving him feeling refreshed and renewed. With closed eyes, He surrendered to the soothing sounds of the waves and the caress of the gentle breeze, allowing them to guide him into a state of calmness and relaxation.”

In My House Is A Boat, she interrogates the issue of climate change, saying:

Once stood proud walls and floors, now embraced by the tide,

As nature weeps, a melancholic guide.

Yet within these watery walls, tales abide,

Of laughter and love, in memories that reside.

Echoes of joy, now silent in the deep,

Yet the spirit of the house, it continues to seep.

Through shattered windows, sunlight may creep,

Reminding us all, strength lies in what we keep.

In Siesta In Makoko, a bustling waterfront community built on stilts over the Lagos Lagoon, lies a silent yet profound presence – logs of wood scattered across the water’s surface. These logs, once towering trees, now serve as sentinels of the community’s resilience and resourcefulness.

“Every log tells a story – of the trees that once stood tall in distant forests, of the hands that felled them, and of the communities that rely on them for survival. They are a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the people of Makoko, who have learned to adapt and thrive in harmony with their watery environment,” she says.

The structuring of the book is commendable and this makes it a good read.