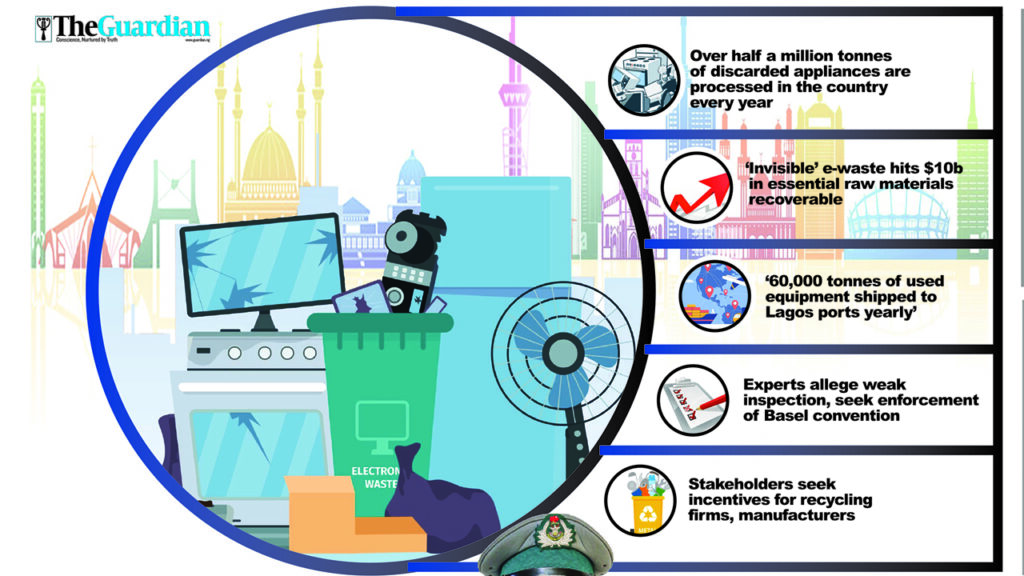

• ‘Invisible’ e-waste hits $10b in essential raw materials recoverable

• ‘60,000 tonnes of used equipment shipped to Lagos ports yearly’

• Experts allege weak inspection, seek enforcement of Basel Convention

• Stakeholders seek incentives for recycling firms, manufacturers

With the high inflation and economic meltdown weakening the purchasing power of Nigerians, many have jettisoned brand new electronics products and relying more on second-hand items, thereby increasing electronic waste in the country.

The Guardian gathered that the current trend has also increased the importation of used electronic equipment into the country, which are mostly discarded products that have reached the end-of-life cycle.

Over half a million tonnes of discarded appliances are processed in the country every year, threatening both the health of people in the informal recycling industry and the nation’s environment. According to a Basel Action Network study, in conjunction with BCC Nigeria, the country imported about 500,000 used computers yearly through the Lagos port alone, that figure has increased with the turn of events.

Nigeria’s piles of e-waste come both from home and abroad. The country generated 290,000 tonnes of electronic waste in 2017 – a 170 per cent increase against 2009. Nigeria remains a major recipient of used electronics from abroad.

While the true amount of overseas-generated waste landing in Nigeria is hard to quantify, United Nations University research has revealed more than 60,000 tonnes of used electrical and electronics equipment are shipped into the country yearly via Lagos ports alone, with an unknown amount imported via land routes from neighbouring countries.

About 25 per cent of the imports are functional used electronics, while the remaining 75 per cent are junk or unserviceable, which are eventually burnt or dumped carelessly. E-waste, any discarded product with a plug or battery, is a health and environmental hazard, containing toxic additives or hazardous substances such as mercury, which can damage the human brain and coordination system.

A preliminary survey conducted in the Lagos area after the study showed that the volumes of imported electronic equipment were Computer Village (15 tonnes), International Market (100 tonnes), Oshodi Market (15 tonnes), and Lawanson Market (30 tonnes) and West Minister (40 tonnes).

Government officials disclosed these figures have reduced drastically as a result of the steps taken to monitor the importation of used Electrical and Electronic Equipment (EEE) into Nigeria. However, civil society groups disagree, saying that the figures have doubled as agencies lacked appropriate mechanisms for monitoring and sanitising the system.

Up to 90 per cent of the world’s electronic waste, worth nearly $19 billion, is illegally traded or dumped each year, according to a report released today by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Each year, the electronic industry – one of the world’s largest and fastest growing – generates up to 41 million tonnes of e-waste from goods such as computers and smartphones.

The International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL) estimates the price of a tonne of e-waste at around $500. Following this calculation, the value of unregistered and informally handled, including illegally traded and dumped e-waste ranges from $12.5 to $18.8 billion yearly.

Also, every year, $10 billion worth of unused cables, electronic toys, LED-decorated novelty clothes, power tools, vaping devices, and countless other small consumer items often not recognised by consumers as e-waste amount to nine billion kilogrammes of e-waste, one-sixth of all e-waste worldwide.

This “invisible” category of e-waste in one place would equal the weight of almost half a million 40-tonne trucks, enough to form a 5,640 km bumper-to-bumper line of trucks from Rome to Nairobi.

The observations aligned with the UN’s fourth Global E-waste Monitor (GEM) which revealed that the generation of electronic waste is rising in the global stock, five times faster than documented e-waste recycling. A record 62 million tonnes (Mt) of e-waste was produced in 2022, up 82 per cent from 2010, and on track to rise another 32 per cent, to 82 million tonnes in 2030.

Nigeria has made significant progress in the management of EEE in terms of policy and legal framework, but a lot still needs to be done in the actual implementation of the EPR.

“As a result of improvements in enforcement and regional collaboration, progress has been reported in the control of illegal shipments of e-waste in West Africa,” says the official. However, in January 2023, an organized crime group was caught smuggling over five million kg (331 containers) of e-waste from the Canary Islands to Ghana, Mauritania, Nigeria and Senegal.

Furthermore, in 2020, the Spanish authorities intercepted a network responsible for shipping 2.5 billion kg of material to several countries in Africa, including 750,000 kg of falsely certified e-waste. Even though the import of e-waste into Africa is being monitored, it is notoriously difficult to control,” according to the 2024 Global Environmental Monitor.

“Three of Africa’s most active ports—Durban (South Africa), Bizerte (Tunisia), and Lagos (Nigeria)—have all been identified as major ports of entry for used EEE, suggesting that e-waste shipments continue to circumvent the Basel and Bamako Conventions.

A study in Ireland that used the StEP Initiative person-in-the-port methodology found that roll-on/roll-off vehicles, rather than containers, were the main carriers of used EEE from Ireland to West Africa.

The study, which involved vehicle and enforcement document inspections at Ringaskiddy port in Ireland, scaled sampling data to yearly shipment figures and estimated that 17,319 kg of used EEE were exported from Ireland annually, and around 1 in 5 vehicles exported contained used EEE.

In response to findings, countries in West Africa are taking steps to introduce better monitoring of used EEE and e-waste imports by strictly enforcing existing guidelines and conducting thorough physical inspections of import shipments.

Under the Nigeria law relating to e-waste control, manufacturers and importers of EEE are expected to partner with the Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) on the Extended Producers’ Responsibility (EPR) Programme to achieve the buyback programme, while importers or distributors for all EEE equipment traded or donated to individuals, educational institutions, religious organisations, communities or body corporate by whatever means, shall comply with the EPR programme.

In 2011, the government passed the National Environmental (Electrical/Electronic Sector) Regulation, which banned the importation of E-waste and provided guidelines on environmentally sound management of E-waste. How this law has been implemented is yet to be seen as various kinds of electronic waste find its way into the markets.

According to the International Labour Organisation, up to 100,000 people work in the informal e-waste recycling sector in Nigeria, collecting and dismantling electronics by hand to reclaim the saleable components. Informal workers are directly exposed to hazardous chemicals and commonly suffer respiratory and dermatological problems, eye infections and lower-than-average life expectancy.

The waste with no economic value is often dumped or burned –releasing pollutants including heavy metals and toxic chemicals (including dioxins, furans and flame retardants), into the air, water and soil. Over 52,000 tonnes of brominated (flame retardant) plastics, 4,000 tonnes of lead, 80 tonnes of cadmium and 0.3 tonnes of mercury are burned or dumped in Nigeria every year.

Statistics show that approximately 100,000 people work in Nigeria’s electronics recycling sector, providing an important source of livelihood. However, this comes at a cost, as breaking down electronic equipment releases persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and mercury, harmful chemicals, which pose risks to human health and the environment.

Already, the Federal Government is driving the e-waste recycling scheme through the E-Waste Producer Responsibility Organisation (EPRON). “The revised regulations bind all manufacturers and importers of electrical equipment, e-waste collection centres, and recycling facilities to register EPRON, marking an essential step towards the operationalisation of a financially self-sustaining circular electronics network,” according to Director General National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) Prof Aliyu Jauro.

“EPR has been on Nigeria’s waste management agenda since the gazetting of the Regulations in 2009. We are making progress.”

With manufacturers, importers and retailers now legally and financially responsible for the management of their waste products, the EPR scheme promotes resource conservation and increased recycling, while encouraging manufacturers to design eco-friendly alternatives.

EPRON Executive Secretary Ibukun Faluy said the organisation’s work has been at the heart of the EPR system in Nigeria, adding “The support from key private sector actors has been valuable to this effort.”

“We now need all manufacturers, assemblers, importers and distributors in the system to come on board and take up their responsibilities to manage the entire lifecycle of their products in an environmentally and socially sound manner,” Mrs Faluyi said.

Experts blame the inefficiency of law enforcement agencies for the flooding of the markets with e-waste equipment. Executive Director, Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development (SRADev Nigeria), Dr Leslie Adogame, said the economy is driving used electronic products due to their affordability. “A lot of importers find it easier to bring e-waste products into the country,” he said.

Adogame told The Guardian that “the end-of-life equipment is seen as waste in the north, and of no second value.” According to him, NESREA can’t monitor importation and sales of e-waste equipment in the country.

He called for capacity building for the NESREA and enforcement agencies in the ports, as well as incentives for recycling firms, and product manufacturers.

Adogame also urged the strict enforcement of the Basel Convention, which is the international trade in hazardous wastes and certain other wastes. Under the trade, there is prior informed consent for the export of hazardous and certain other waste to importing countries.

The Chairman, Nigerian Environmental Study Action Team (NEST), Prof. Chinedum Nwajiuba, advocated a review of the regulatory framework for e-waste imports into the country.